I’m on a study project to improve my understanding of roleplaying games. To this end, I already have two reading projects, A Game Per Year and An Adventure Per Year. This is the third, with the goal of reading or playing 52 games made in the last few years. Originally I considered making this “A New RPG Per Week” and that’s where the number 52 comes from, even though a weekly schedule is probably not within my abilities.

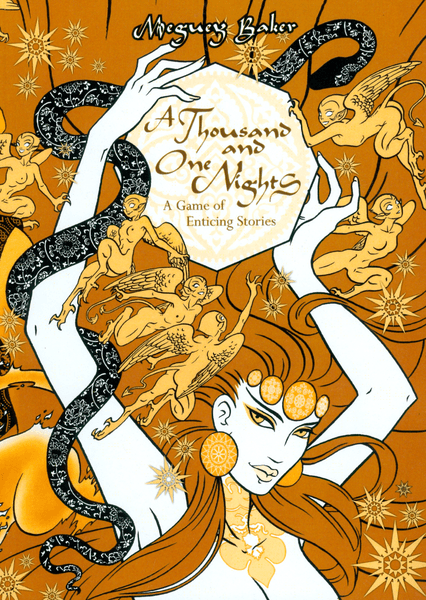

Meguey Baker’s A Thousand And One Nights (the 2012 edition) is a game in the tradition of American storygames, maybe more “storyish” than most! Sometimes I find it difficult to separate whether “story” in discussions of roleplaying games refers to the mechanics of how narratives are constructed or the aesthetics of stories and storytelling.

Here it’s definitely the latter. As the example of play shows, the story produced by the game can be a total mess. What matters is the experience of “storyness”, dealing with stories, that is in itself aesthetically pleasing. We like the mystique of storytellers and their tales and find it pleasing to inhabit that role.

A Thousand And One Nights is a game about courtiers in the Sultan’s court in an exoticized, timeless faux Arabic fairytale world. They tell stories to maintain their status and safety and get at their rivals. Thus, you play a character who tells a story. When you do this, you assume a GM role and assign the roles of the characters in your story to the other players/characters who can use the opportunity to subtly further their own goals. Naturally, a story can have a substory, leading to a nesting structure where the shape of the game you play and the in-game fiction mirror each other.

It’s an ornate, fun structure really going all the way with the “Once upon a time” and “Let me tell you a tale” romanticism. It rewards cleverness and being able to communicate insults and supplications with a metaphor and a raised eyebrow.

The very first sentence of the game book is this: “This is not a game about Arab culture.” It’s explicitly framed as being informed by American childhood stories of the Arabian Nights and the magic experienced therein, not the lived reality of actual Arabs. It’s purposefully exotic: “We need the exotic, the fantastical, to lift us out of ourselves, out of our everyday experience. We need to delight in what is not familiar, exploring it for what it is – a strange and wonderful world not our own.”

It’s an interesting framing especially considering that the game was published just a few years before the cultural appropriation discourse exploded.