I’m on a study project to improve my understanding of roleplaying games. To this end, I already have two reading projects, A Game Per Year and An Adventure Per Year. This is the third, with the goal of reading or playing 52 games made this year or last year. Originally I considered making this “A New RPG Per Week” and that’s where the number 52 comes from, even though a weekly schedule is probably not within my abilities.

Troika! is a British roleplaying game designed by Daniel Sell. It’s a surreal game with character classes such as the Epopt and Befouler of Ponds. On its Kickstarter page, the designer Patrick Stuart is quoted describing it as “Hipster Planescape”.

In style, Troika! is an OSR game with a focus on the kind of chaos you get when you have surreal world elements and a lot of random chance. The system is simple and most of the book is reserved for three things: character classes, spells and monsters.

I’m not in the OSR scene myself so I’m not entirely familiar with all the nuances of the playstyle. Because of this, the experience of reading the book was cryptic. I kept thinking how to use all these bizarre elements in a game. However, fortunately the book ends with a sample adventure that clarified a lot of the confusion.

In the adventure, the characters (let’s say, a party consisting of a Zoanthrop, a Vengeful Child and a Fellow of the Sublime Society of Beef Steaks) meet in the lobby of the hotel Blancmange & Thistle. Because there’s only one room left, they have to share it and thus get to know each other.

The rest of the adventure consists of the encounters they have while using the elevator or the stairs to reach their room. The book also contains a table of adventure seeds which follow a very traditional quest-based structure.

A classic problem with participatory media is that unlike with spectator media, participation requires creative buy-in from the participants. For the game to work, they have to be able to engage with it as creative participants. This creates a problem for works that go for weirdness or surrealism: If things are too surreal, the players are paralyzed because they have no idea what to do.

In Troika!, the traditional model of quests and thin characters acting as player proxies makes the weirdness palatable. You may not know what a Khaibit is but you understand how to play the game.

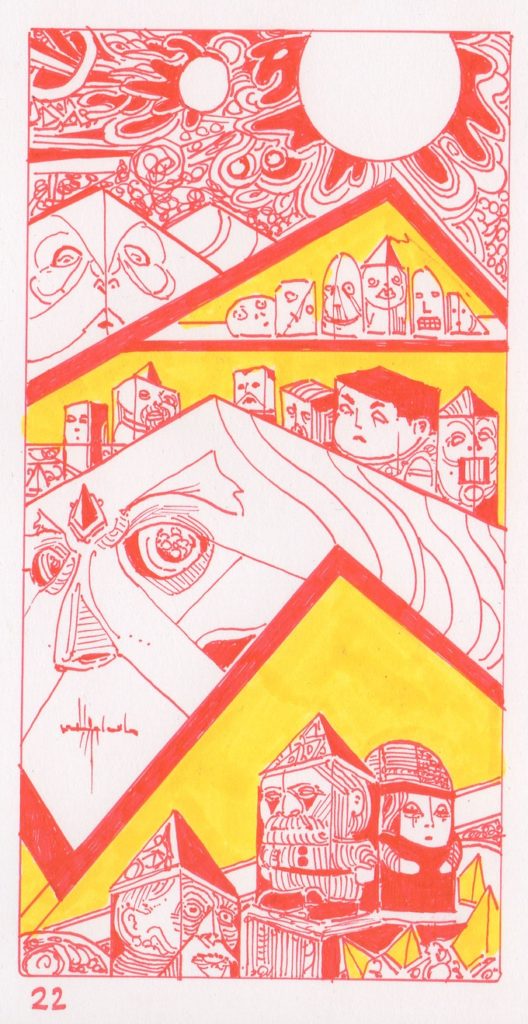

As a book, Troika!’s most distinctive feature is the art style. The game has a powerful, unique visual identity that sets it apart from much of the roleplaying game field. Considering that in roleplaying games, visuals often draw from a fairly small, conservative pool of influences, this is extremely welcome.

As a final note about Troika!’s system, it has a clever initiative system I’ve never seen before. Initiative is often a foil for game designers because in combat scenes broken down into rounds it’s seen as necessary to have a system for who goes first, yet in practice using such systems often fails to contribute to the game in an interesting way.

In Troika!, every player character has two beads and the GM has a pool of beads the size of which is determined by the number of enemy NPCs and creatures. All beads are poured into a container with a special “end of round” bead.

The way initiative works, beads are picked and the character who’s bead comes up gets to act. If the GM gets a bead, they can choose which enemy acts. When the “end of round” bead comes up, all beads are returned to the container and the next round begins.

This is a significantly more chaotic system than more traditional initiative mechanisms but it also produces dramatic, interesting results. Maybe your character gets to act twice at the beginning of combat. Or maybe they don’t get to act at all and all the enemies just pile on you.