I started to feel that I didn’t know roleplaying games well enough so I came up with the plan to read a roleplaying game corebook for every year they have been published. Selection criteria is whatever I find interesting.

Dream Park is a roleplaying game based on the series of scifi novels by Larry Niven and Steven Barnes. The setting of the novels is the titular Dream Park, an amusement park of sorts where people participate in experiences that resemble larp or reality tv.

Westworld is a great reference point but Dream Park’s style is more competitive and points-oriented, more Survivor than psychodrama.

The unique nature of the setting was the reason I read the game. I thought it would be interesting to see how a game about people playing a game would work. After all, the player characters in a Dream Park game are players who go to Dream Park to play a game.

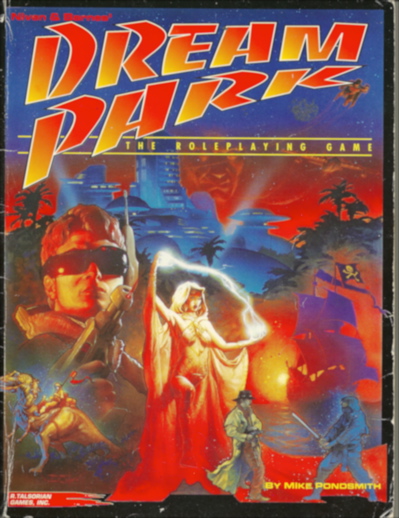

Designed by Cyberpunk guru Mike Pondsmith, Dream Park uses a variation of the same system, only adapted to a much wider selection of possible settings. After all, a Dream Park character can be a superhero in one session and a Western hero the next, depending on the games they go to inside the fiction.

Indeed, when you read Dream Park, it feels like the main attraction of the license wasn’t the specifics of the Dream Park IP or the “game-within-a-game” setup, but the possibility of doing a multigenre game.

In the early Nineties, this was certainly in the air. Games like Rifts and Torg were all about different realities and settings. Dream Park feels like an excuse to use the license to craft a system that can serve all kinds of adventure games.

This is apparent in the game’s design. The rules cover dogfights and combat between battleships but the question of what to do with the game’s multiple layers of fiction gets only cursory notice. This despite the fact that the theme of reality intruding into the games is a major element of the original Dream Park novels.

Dream Park serves three distinct design goals:

- Make a roleplaying game based on the Dream Park novels.

- Make a beginner-friendly roleplaying game.

- Create a universal design that works with all genres and settings.

Unfortunately, these goals are in conflict with one another. Dream Park is an intricate, challenging setting, strange for a beginner’s game. Privileging the creation of a universal design means ignoring the specific demands of the Dream Park setting.

Still, there are a few interesting design ideas. Each character is split into two parts, the player and the role. The player is a constant while the role can change depending on the adventure the player is currently playing.

(Basic terminology such as player and character gets confusing really fast in this setup.)

The player is the person who goes to Dream Park inside the fiction. They have one set of stats. They also have points they can use to buy new characteristics for their temporary character inside each individual game they participate in. This way, character creation doesn’t happen just in the beginning of the roleplaying game campaign, but inside the fiction each time the character signs up for a new Dream Park experience.

Another fun characteristic of the setting is that there are Game Masters also inside the fiction. The book recommends having a variety of Game Master NPCs, each with their own styles, so that people can form social relationships with them.

To me, this is an example of the kind of potential for weird metacommentary on roleplaying games that the Dream Park setting makes possible.