I’m on a study project to improve my understanding of roleplaying games. To this end, I already have two reading projects, A Game Per Year and An Adventure Per Year. This is the third, with the goal of reading or playing 52 games made in the last few years. Originally I considered making this “A New RPG Per Week” and that’s where the number 52 comes from, even though a weekly schedule is probably not within my abilities.

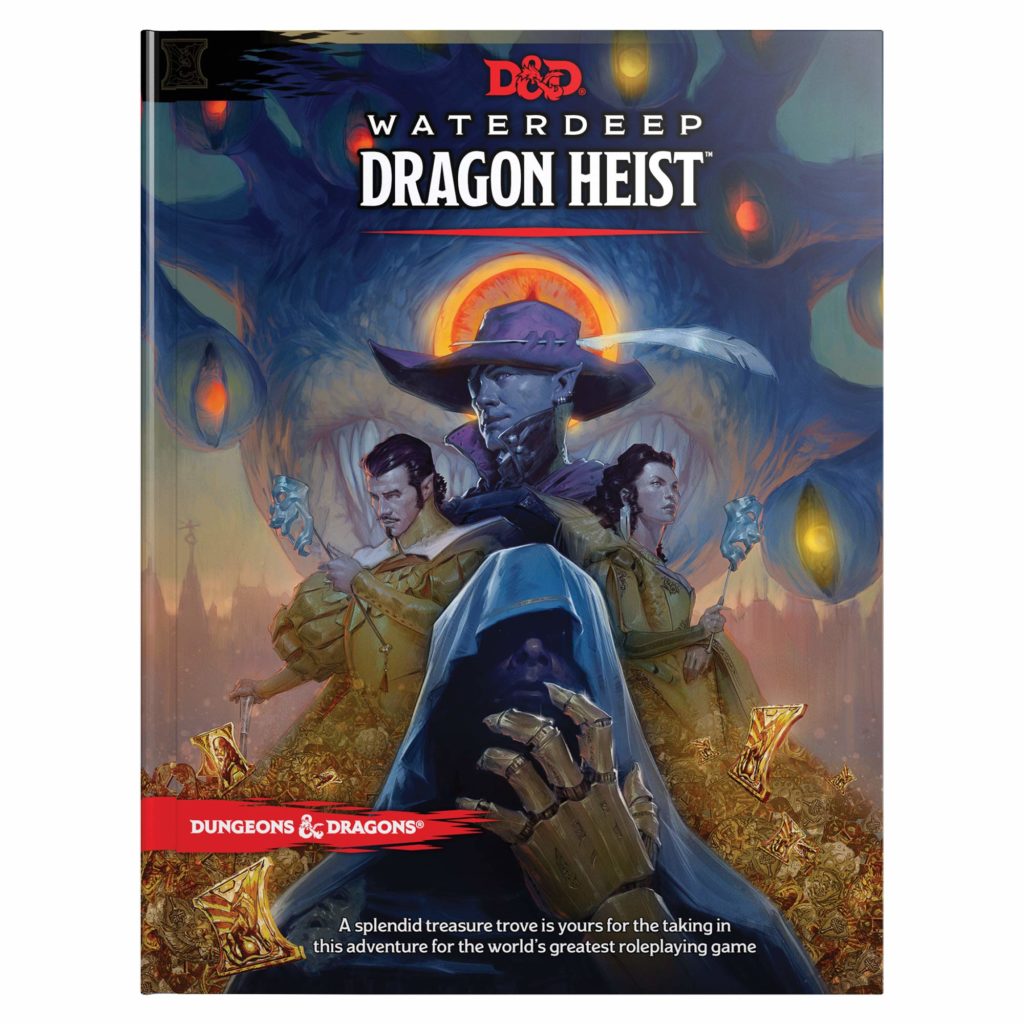

Waterdeep: Dragon Heist is an adventure published for D&D 5th Edition. It’s the first in a two-part series, followed by Waterdeep: Dungeon of the Mad Mage. Dragon Heist showcases many of the trends of 5th Edition design as well as larger pop culture trends especially in the American media landscape.

The publishing strategy for 5th Edition has been markedly different from earlier editions, such as the 3rd. Essentially, the 5th Edition is a best of -collection of past glories and marketing tie-ins. I don’t say this as a bad thing, necessarily. Wizards of the Coast publishes just a few flagship books every year and they are very well made, some of the highest quality work you’ll find on the roleplaying game market.

This is in marked contrast to earlier editions where it sometimes felt difficult to separate the good stuff from a flood of junk.

The Waterdeep series revisits the most famous city in Forgotten Realms, the titular Waterdeep. Dragon Heist is an entry level adventure where characters run around the city looking for a hoard of gold while the sequel takes the characters to the megadungeon Undermountain, situated under the city.

In tone, Dragon Heist is more lighthearted than some of the other 5th Edition material I’ve seen. The world feels more steampunk-inspired and less high fantasy, with broadsheets, mechanical automatons, gunslingers and characters with names like Vincent.

The adventure has an interesting design. It presents four different options for the main villain and the flow, tone and content of the adventure changes a lot depending on what the DM chooses. Some villains are more serious, other frivolous. One seems designed for players who are not really interested in the story of the villain.

This means that the DM is forced to customize the adventure, something I always like.

For a D&D adventure, another design choice is that characters are not assumed to murder everything in sight. Many of the enemies are too powerful for the characters to kill in a straight fight and the objectives of the adventure don’t require them to do so. I liked this element of the design as well.

After all, talking is the easiest thing to simulate around a gaming table.