I’m on a study project to improve my understanding of roleplaying games. To this end, I already have two reading projects, A Game Per Year and An Adventure Per Year. This is the third, with the goal of reading or playing 52 games made in the last few years. Originally I considered making this “A New RPG Per Week” and that’s where the number 52 comes from, even though a weekly schedule is probably not within my abilities.

The King in Yellow is a horror character created by the writer Robert W. Chambers, an alien ruler with a mask-like face. He spreads the malign influence of his home reality of Carcosa by disseminating a play about himself.

The character of the King in Yellow has been subsumed into the Cthulhu Mythos by later writers but the original stories by Chambers have nothing to do with Cthulhu. Indeed, he published them when Lovecraft was still a child.

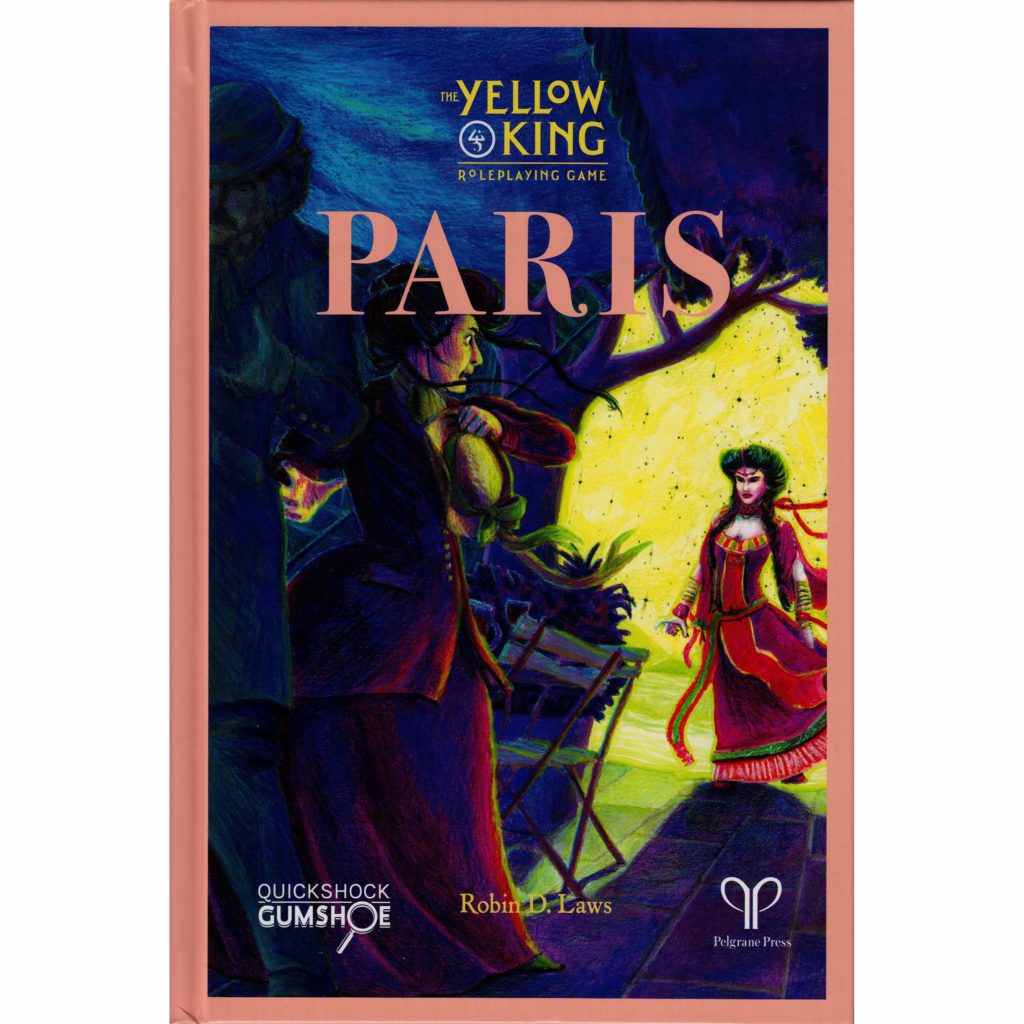

The Yellow King is a roleplaying game by the veteran designer Robin D. Laws. It’s explicitly based on the original Chambers stories, ignoring the later convergence of horror fiction around the Cthulhu Mythos.

The Yellow King is an impressive achievement. Based on the Gumshoe system which is designed for investigation-based games, it comes as a set of four books housed in a slipcase that opens up into two GM screens (!!!). It’s pretty cool.

Each of the four books details a new setting in which the characters can try to unravel the reality-breaking mysteries of the Yellow King. The original concepts associated with the King are wonderfully evocative. White sky with black stars, the fatal play, the King and his daughters Camilla and Cassilda, the Lake of Hali. (Hali is a cute word for hug in Finnish.)

The first setting introduces the characters as art students in belle epoque Paris. Played out in full, The Yellow King is meant to be experienced as a series of four campaigns, each mirroring the last in terms of themes, characters and ideas. It’s an ambitious, grand design.

Paris is followed by The Wars, an alternate reality world war setting in which the characters are soldiers trying to survive in the trenches. In the third campaign, Aftermath, the dictatorial rule of Carcosa-backed Hildred Castaigne has ended and the characters are left to pick up the pieces in an alternate-reality U.S. The last setting is called This Is Normal Now and features a modern world with the characters as ordinary people drawn into Carcosan mysteries.

I found the Aftermath setting the most interesting one. I haven’t seen the milieu of a country freeing itself from dictatorship explored in roleplaying games before. In addition to investigation, the setting also features politics. The characters can enter the new-born democratic process and try to get one of them elected. There’s a system for advancing specific values and goals. For example, you might be for or against the public suicide chambers left by the Castaigne regime.

Aftermath is set in a U.S. that’s smaller than the real-world version, sharing the continent with two other countries in addition to Canada and Mexico: California and Suanee. The latter is located in the South-East of the continent. In Suanee, all white people were subjected to supernatural ethnic cleansing, leaving a country of people of color. Many people of color living in the U.S. moved to Suanee, leaving the U.S. whiter than before.

Gumshoe is a system for games focusing on investigation and it’s famous for one specific rule: The characters always find the clues they need to progress. If they’re in the right place and even marginally applying themselves, they’ll get it. The system makes sure of it.

I’ve played in games where investigation has stalled because we haven’t found the right clues so I appreciate this idea.

To be precise, the system is a streamlined version of standard Gumshoe. It has two other features that I liked, a very functional, quick combat mechanism and a detailed, card-based system for physical and mental shock. The combat mechanism is based on a simple roll which determines who achieves the goals they set out for themselves. It’s explicitly not about killing your enemies.

Shocks are expressed as cards, each with their own bespoke effects. Thus, each wound is a little different, and to get rid of it you need to do different things. Once you have too many cards in your hand, your character dies or is too traumatized to continue.

The way American pop culture has normalized torture is one of my personal pet peeves so I was delighted to see that the system gives you a mental shock card for both enduring and perpetrating it. Being a torturer degrades you in game mechanical terms.