In my A Game Per Year project, my goal has been to read one roleplaying game corebook for every year they’ve been published. However, I soon started to feel that it was hard to decipher how the games were really meant to be played. For this reason, I decided to start a parallel project, An Adventure Per Year, to read one roleplaying adventure for each year they’ve been published.

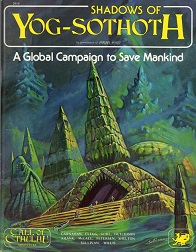

Shadows of Yog-Sothoth is an adventure campaign published for Call of Cthulhu in 1982. I read it in the 2004 edition although I also had the opportunity to leaf through the original.

The campaign is set in the Twenties and begins with the Investigators joining the Hermetic Order of the Silver Twilight. From there they go onto a series of loosely connected adventures in Scotland, Easter Island and R’lyeh, eventually facing down the prospect of an awakened Cthulhu itself.

In terms of design, the adventures are a far cry from the dungeon explorations of D&D. This time, the main focus is on investigation and the gathering of clues before violence breaks out. This means talking to NPCs, the descriptions of which are significantly more sophisticated than in the adventures I’ve read previously as part of this project.

Reading the campaign, I started to think that one concept which is taken for granted in roleplaying games is “player character”. Game books tend to assume we understand what that means even though the meaning of “player character” changes enormously from game to game.

For example, the adventuring party of a D&D game is a very specific, idiosyncratic concept. The Investigators of Call of Cthulhu also come with a whole bunch of assumptions about how they behave and what they do. If those assumptions are not followed, the game breaks apart.

To me, this is noticeable because my local roleplaying scene developed its own approach to player characters, privileging an emotionally immersive portrayal of a complex personality. On the surface, if you read incautiously, this is what many roleplaying games seem to be suggesting as the standard model. However, contact with other roleplaying scenes and reading many game books has made me understand that our approach is not standard at all but merely just a niche approach among many, many others.

Indeed, in a campaign like Shadows of Yog-Sothoth the approach typical of our scene would make the game unplayable since the adventure requires a certain comfort with the disposable nature of the player characters. They are expected to be suicidally brave as a matter of course.

The design of the scenarios which comprise Shadows of Yog-Sothoth is very variable. Some are complex social sandboxes, such as the Silver Twilight lodge and a Scottish village. Others are random monster encounters. There’s an extra adventure in the appendix which is basically a dungeon complete with treasure and a secret door.

I’ve played a lot of Cthulhu-inspired boardgames such as Arkham Horror. The way the Cthulhu Mythos is described in those seems to draw much more from the materials published for Call of Cthulhu the roleplaying game than Lovecraft’s original stories. Books like Shadows of Yog-Sothoth present a pulp adventure with a coherent mythology, a style which characterizes many Cthulhu games of latter years.

I remember struggling with this campaign, which forced some improvisation. Given the lethality of it, and that I only had 2 players, we wound up creating A and B Team investigator groups who both followed the tracks of the conspiracy in alternating sets of adventures. The death of the B-team re-inforced the lethality of the campaign to the players, while allowing their A-team investigators to make it to the end. In terms of psychological depth, I wound up mixing in some Fight Club – one of the A team read the Greek Necronomicon early, and while he thought he suffrered from narcolepsy, he had instead developed an alternate personality known as Carl Stanford – a fact not revealed until the finale….