I’m on a study project to improve my understanding of roleplaying games. To this end, I already have two reading projects, A Game Per Year and An Adventure Per Year. This is the third, with the goal of reading or playing 52 games made in the last few years. Originally I considered making this “A New RPG Per Week” and that’s where the number 52 comes from, even though a weekly schedule is probably not within my abilities.

Who tells the story of a Hero? The Hero themselves or the people around them, each with their own perspective?

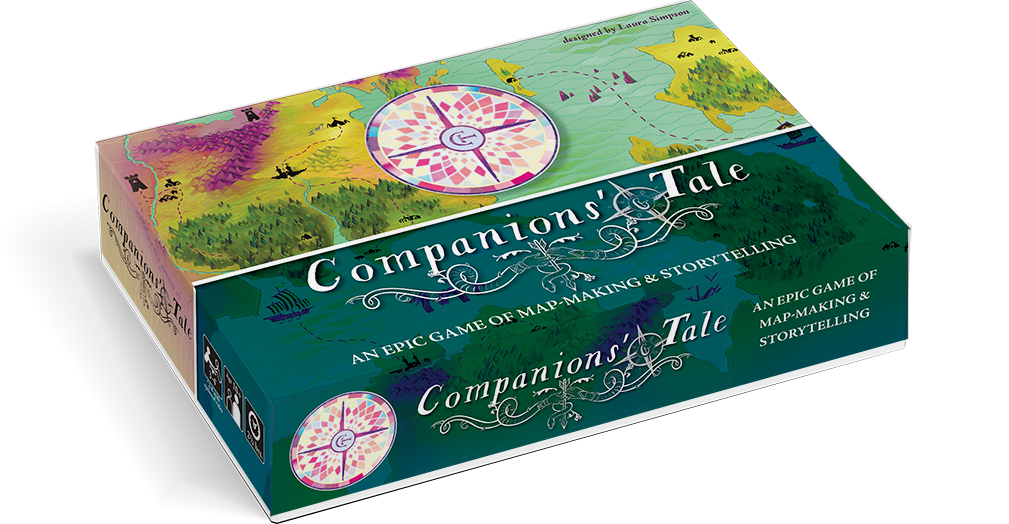

Companion’s Tale is the game that engages with how stories are born and myths created on the human level more than any other game I’ve read. Designed by Laura Simpson, it presents the emerging fiction both as an emergent physical map and a series of stories that don’t have to be in harmony with each other.

Its characters are the people around a Hero, mentors, friends and followers who are there to see what really happened.

The players take on a rotating series of game functions which determine how they contribute to the fiction. For example, the Cartographer updates the map while the Witness provides context by coming up with events in places where the Hero is not. One of the most interesting roles is that of the Biographer who represents the viewpoint of those who come later, often completely distorting what actually happened.

Worldbuilding and culture design are also folded into the process. Both emerge as the game map acquires more details and the players fulfill their functions by providing more detail.

The game uses cards for prompts, giving ideas for themes and characters. Unfortunately, I only had the PDF at hand, and from the photos of the game and the design it feels like tactility and the physical presence of the components is an important quality in the experience.

The game simulates a process where the story of a Hero is born, first by establishing some backstory, then accumulating narrative details in a series of rounds and finally creating an epilogue. Nobody plays the Hero and their presence seems almost symbolic, structural, compared to all the other cool stuff produced by the design.

The game exhorts the participants to avoid consensus many times. If the stories of two players don’t match in all their details, that’s life! When stories are told of heroes in real life, the details rarely match either. From a theoretical standpoint, I find this very interesting because it embraces the idea of a non-coherent fiction. Usually in roleplaying games we try to keep the fiction the same for all players (that is, all players agree that X, Y and Z are true in the game world) but not this time.