I’m on a study project to improve my understanding of roleplaying games. To this end, I already have two reading projects, A Game Per Year and An Adventure Per Year. This is the third, with the goal of reading or playing 52 games made in the last few years. Originally I considered making this “A New RPG Per Week” and that’s where the number 52 comes from, even though a weekly schedule is probably not within my abilities.

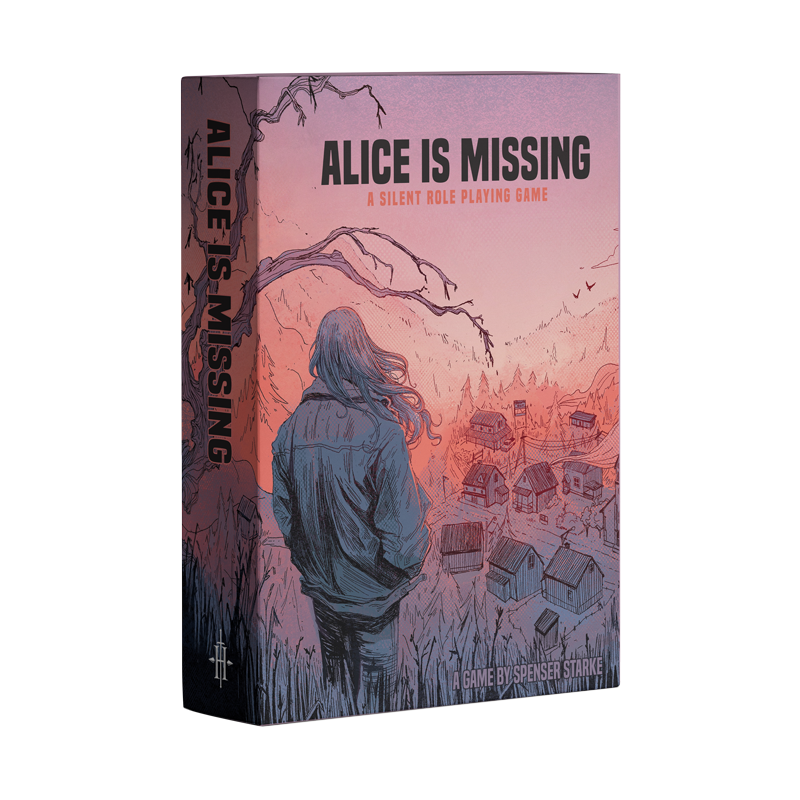

Alice is Missing is a non-verbal, text message based roleplaying game by Critical Role producer Spenser Starke. It’s a GMless one-shot experience that can be played in a couple of hours. Physically, it takes the form of a little box with an instructions booklet and a deck of cards.

The setup of the game is elaborate, including card-based character distribution, changing participant names in your phone’s contacts to those of the characters and using the online timer and soundtrack, here. Because of all this, it’s not a casual game. You have to commit to it and the intricacies of its design.

One of the questions I always find interesting in roleplaying games is where is the design located. For example, it can be expressed as game mechanics and setting information in a big book. Or, as is the case here, it can be in a card deck, booklet and timer video. The design guides the game experience but there are a myriad ways to convey it.

Alice is Missing is a classic story of a missing girl and friends who look for her. The cards and random chance guide how events shape up, with a facilitator who’s job is limited to organizing and caring for the play event. The players are not allowed to talk, instead communicating as their characters in a group chat and via private text messages. However, by default the players are in the same physical space (although there is an online variant), allowing them to see each other’s reactions.

The card deck handles a lot of the work that in other games might be assigned to the GM. There’s something interesting about how creative power and authority is distributed in games with a GM and games without. If our vantage point is at the level of the individual game session, a GMless game is democratic. Everyone has the same ability to influence the fiction.

If we lift our vantage point higher, to the level of roleplay culture, the picture changes. Looking at it from here, a GMless game privileges the creative power and authority of the game designer by removing the GM, a creative middleman. Designer vision stands unchallenged by annoying local variations. (Unless, of course, the whole group of players decides to change the game to suit their own purposes.)

Alice is Missing feels like it’s designed to within an inch of its life. You don’t dare to change anything for fear of toppling the intricate machine.

I’ve played Alice Is Missing twice now, both times in the facilitator role and both times using the online roll 20 version. I’d say your assessment that it’s designed within an inch of its life is probably about right. There is definitely not much room to change things without it having a whole lot of run-on consequences. That said, I do alter things a little by guiding players away from the “make jokes and break the tension” instructions on some of the cards. I tend to prefer to lean into the fear and anxiety for a more intense experience. With just that small change, it delivers that intense emotional experience in spades.