I’m on a study project to improve my understanding of roleplaying games. To this end, I already have two reading projects, A Game Per Year and An Adventure Per Year. This is the third, with the goal of reading or playing 52 games made in the last few years. Originally I considered making this “A New RPG Per Week” and that’s where the number 52 comes from, even though a weekly schedule is probably not within my abilities.

Paranoia had a huge influence on roleplaying culture when I first got into the scene in the Nineties. Jokes about the Computer were everywhere. Our local con Ropecon had a Troubleshooter team. If you were interested in roleplaying, you had to know Paranoia to get all the in-jokes.

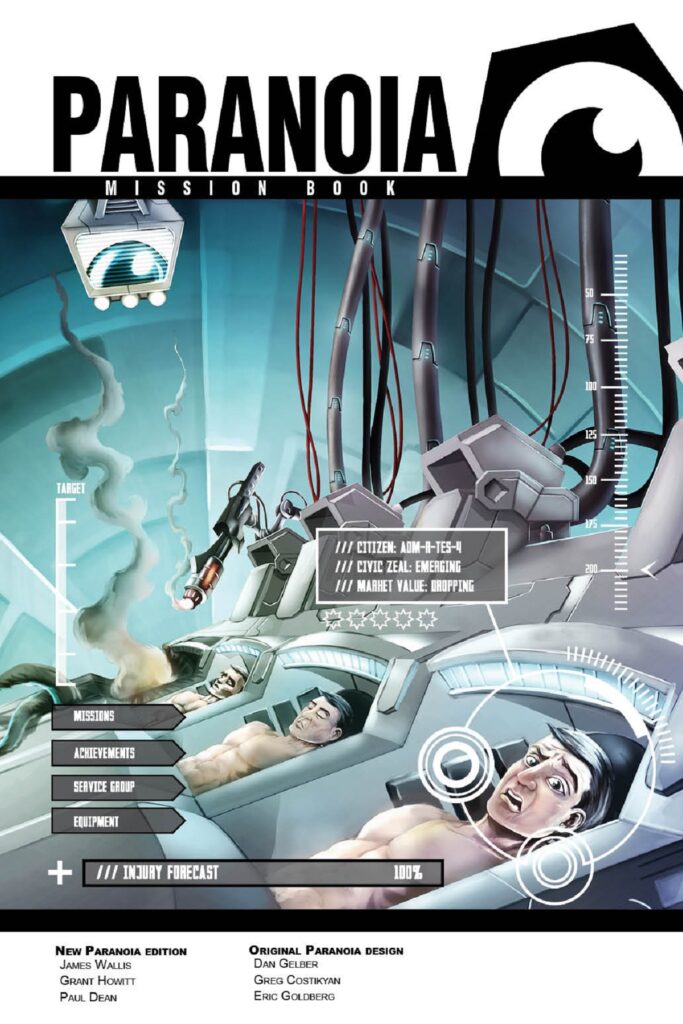

This is the newest Paranoia edition, a white box released in 2016 I got by backing it on Kickstarter. The basic premise is the same as before: The characters are a group of Troubleshooters tasked by the Computer to root out mutant traitors in the utopian Alpha complex. The trouble is, all the characters are secretly mutants and belong to a secret society that makes them traitors.

The characters have Cerebral CoreTech, implants that allows the Computer to see everything they see and speak to them at all times. They have HUD overlays in their field of vision complete with direction arrows so big they obscure what they’re trying to look at. XP is an in-game concept: As the characters complete missions, they’re awarded with XP they can use to raise their security level or buy equipment.

The game’s XP guidelines feature something I’ve never seen before: Instructions for the GM on how to award XP points (the game explicitly tells you to call them “XP points”) in a dramatically appropriate way. Importantly, the GM is told to calculate awards so that the characters are always left just below the threshold of being able to go up a level. This makes XP into a dramatic and psychological tool in a much more conscious way than is usual in roleplaying games.

Another fun example of emotional design is a card that you can give to a player when they do well. It has no game mechanical benefits. It’s just a visible status marker. Then when someone else does good, the GM takes back the card and gives it to them instead.

This type of emotional design is criminally underused in roleplaying games, whether in service of satire or some other goal.

Character creation has also been designed to provide the basis for lingering little resentments between players that they can then take out on each other’s characters. Since betraying each other is part of the Paranoia experience, the game seeks to lay the groundwork for players to feel that it’s okay to do so.

The reason Paranoia endures while many other comedy roleplaying games have been forgotten is that it’s about something real and recognizable. It’s about the irrational nature of power, authority and bureaucracy. The setting is fantastic but pretty much everyone has experienced something in their lives that makes the game’s absurdity relatable.