I started to feel that I didn’t know roleplaying games well enough so I came up with the plan to read a roleplaying game corebook for every year they have been published. Selection criteria is whatever I find interesting.

It feels like over the years the emotional landscape of science fiction and fantasy have changed almost completely. Purportedly, these genres (and horror as well) are all about the new, the uncanny, the wondrous, the unfamiliar. We explore these strange worlds and marvel at the miracles within!

And perhaps at some point, these genres really offered such pleasures.

Now, the function of genre tropes is to offer us something safe and comforting, familiar and unthreatening. If we have a roleplaying game that deals with serious real-world issues, we can distance ourselves from the experience by introducing genre tropes that make it more palatable and less emotionally uncomfortable for us.

It often feels like game mechanics serve a similar distancing effect. During play, you can retreat from the emotions and subject matter at hand by focusing on the mechanical side of the game.

A friend once told a story about failing at D&D because she went the other way, insisting on re-introducing the emotional and subjective experience to a scene that was supposed to be resolved solely through genre conventions and mechanics. When her character looted a body, she described it in detail: “I shudder, close to vomiting, as I seek to sneak my hand into the bandit’s pockets, trying not to look at the grotesque wound bisecting his belly, excrement from shredded intestine mixing with blood…”

She said she had to leave the group because it was felt she didn’t play within the spirit of the game. Which was true.

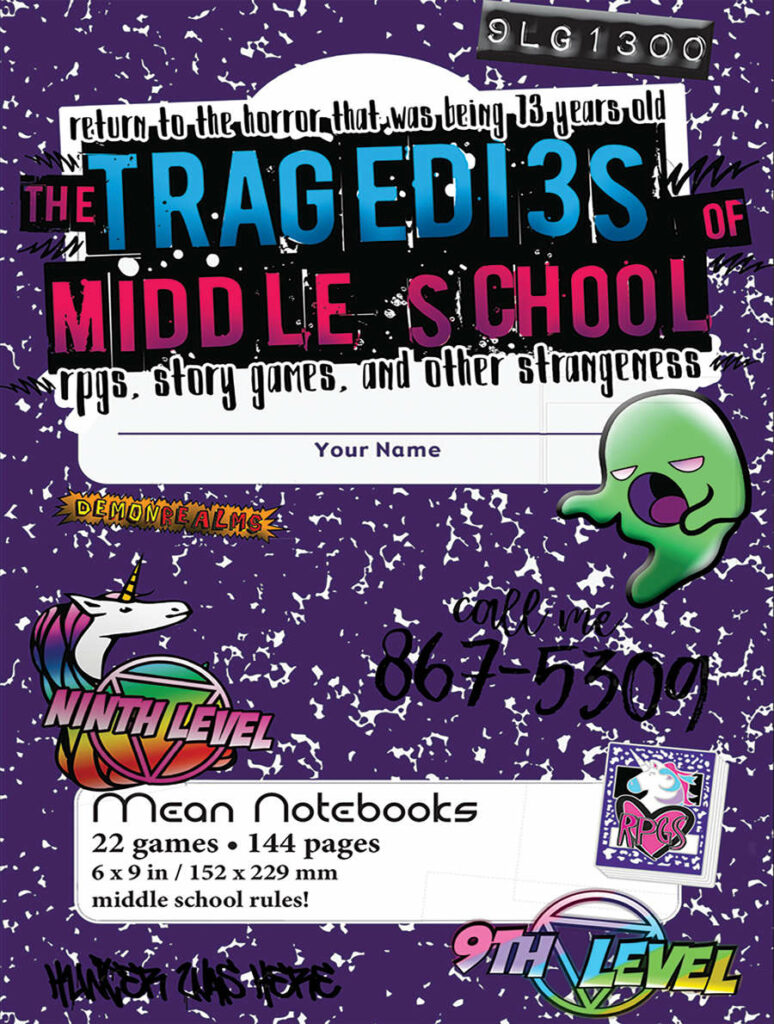

The Tragedies of Middle School is a collection of 22 roleplaying games, larps and other, less quantifiable analog social games. There’s even a Choose Your Own Adventure -style solo game. Reading the games reminded me of these two methods for distancing participants from serious subject matter, both at play here.

School life can be terrifying and bizarre from the perspective of life and that fact informs many of the games here. Yet they’ve also been designed in a friendlier way than a Fastaval bleed-fest, allowing their players to keep their emotions at an arms length.

An example is the first game, Seven Minutes in Hell, which gets its power from the archetypical setting of an 8th grader house party and then spins off into demonic possession. It also shows that sometimes a bit of distancing can be desirable. It allows us to have fun with the awkwardness lurking in our own pasts.

The games are lighthearted even when they’re serious, some of them simple sketches of game ideas that you can try out in half an hour. They’re described briefly and efficiently, with little in the way of solid rules text. The visual design of the book conveys atmosphere.

Some of my favorites in the collection come near the end, where all the stranger games lie. Social Darwinball is a re-designed version of dodgeball and Is There a Spider On My Head? is a simple card game of lying, bluffing and reflexes.