I started to feel that I didn’t know roleplaying games well enough so I came up with the plan to read a roleplaying game corebook for every year they have been published. Selection criteria is whatever I find interesting.

I didn’t know anything beyond the basic concept about Gangbusters when I decided to read it for the 1982 entry in this project. It proved to be one of the most interesting games I’ve gone through so far, alongside earlier favorites like Empire of the Petal Throne and Metamorphosis Alpha.

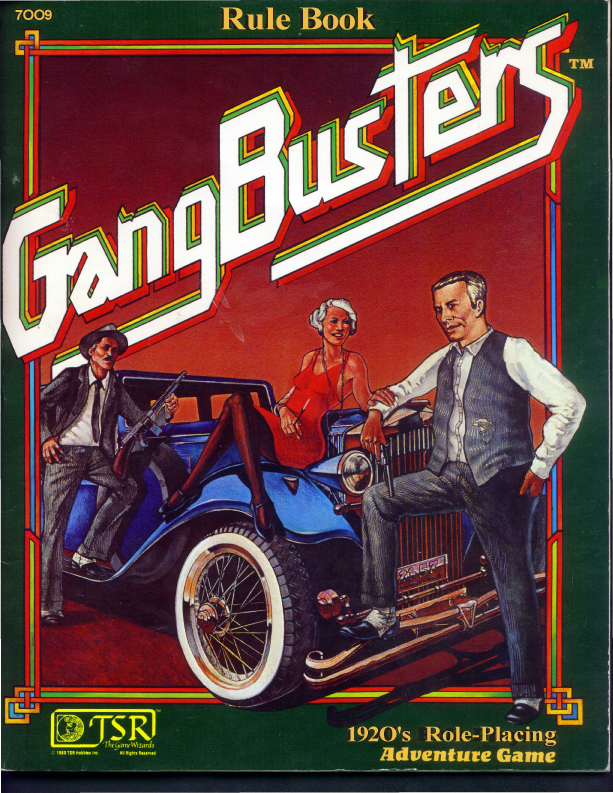

Gangbusters is a roleplaying game about American crime in the Twenties and Thirties. Cops and gangsters, Al Capone and Elliot Ness. As befits the early 80’s design style, it’s heavy on simulation and light on narrative elements, character immersion or mood.

One of the most interesting core ideas of the game is that players are expected to play against one another, not as a single cohesive team. For example, if the game features two cop characters and two gangster characters, they make up two sides. The wild card character type presented in the game is the reporter who can investigate actions on either side of the law.

There’s two game modes, simple scenarios and a campaign. The scenarios are all about simulating physical reality in classic genre situations. For example, two gangsters are trying to rob a jewelry store. Two cops show up. A shootout ensues. This mode is almost like a boardgame, complete with maps and cardboard figures to represent the characters.

The campaign mode is where the real action is. Its basic unit is the week. Characters make plans in weekly increments and when those plans lead to scenes or conflicts, those are played out in more detail. This is done in an adversarial fashion: If the cop characters manage to suss out the details of the proposed bank robbery, that can then be played out as a fight scene.

This means that the game features extensive rules simulating life on a societal level. There are intricate systems for running bootlegging operations, bookmaking, loansharking, etc. As characters gain levels, they get promoted. At the beginning of the game they’re small-time hoods and beat cops but by the end they run either the local police as the commissioner or a huge criminal empire.

The reporter ends up as the editor-in-chief, of course.

The characters are expected to make money. They have to pay rent and other expenses and if their source of income dries up, they end up on the street. Criminal enterprises are extremely lucrative but also risky. Cops can make money on the side by taking bribes.

There’s something very elegant and purposeful about all these systems for criminal activity. The game focuses on a clear set of actions mandated by the genre and then provides tools for how to make those things happen. There are tables for police corruption and explanations for how the economic fortunes of the country affect criminal enterprises.

This is the first game I’ve read during this project that tries to sell the fiction and the concept to the player. Before, all the game books have pretty much started with: “Here’s a bunch of rules. Make do.” This time, there’s a little fiction piece about a shootout and a foreword written by a grandson of a member of the Untouchables.

In terms of presentation, the game is a first in another way too: Reading it, it’s possible to grasp how to play it. This sounds obvious, but a lot of the early roleplaying games were so steeped in the culture they sprang from, they’re hard for an outside reader to understand. In Gangbusters, the whole setup is clean and straightforward despite the complex intricacies of the simulation.

Gangbusters was a positive surprise with a lot of interesting ideas. The week-based campaign mode is something that might actually be fun to play even now.