I started to feel that I didn’t know roleplaying games well enough so I came up with the plan to read a roleplaying game corebook for every year they have been published. Selection criteria is whatever I find interesting.

I’m done with the Seventies! If I were to try making a broad, sweeping statement about the stylistic progression of roleplaying games, there’s two distinct phases. In the first one, that of the earliest roleplaying games, the focus is on game design and the exploration of this new creative space. Examples of this are Dungeons & Dragons and Metamorphosis Alpha.

In the second phase, which starts as the Seventies near their end and roleplaying games are starting to become an established phenomenon, the focus moves from game design to using game mechanics to simulate aspects of reality. This is often called realism, although I hesitate to use the word because the games are often highly unrealistic in many aspects of their portrayal of the world, especially with social situations and big-picture things like politics.

This shift in focus represents an interesting aesthetic concern. At least when reading these games now, it feels as if the original goals of game design (making a good, playable, functional game) are sidelined in favor of values that make the games harder to grasp. Clearly during this period, using game mechanics to model aspects of physical reality was more compelling than fun, story or playability.

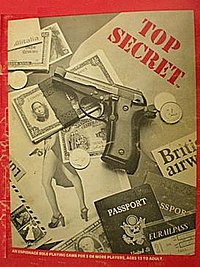

I don’t necessarily mean this as a negative or snarky comment. The first game of the 80’s, Top Secret, demonstrates that although this method of design is intimidating, it can lead to interesting results.

Top Secret is a game about secret agents in a slightly more down to earth style than seen in James Bond movies. But only slightly. The core rules contain minutely detailed mechanics for things like unarmed combat and two people wrestling over the possession of an object, such as a suitcase with nuclear launch codes.

There are some interesting game design concepts. Characters have points they can use to escape certain death or other terrible fates, in an early example of a system which grants some narrative control to the players. The initial number of these points is rolled randomly and is only known by the GM, or the Admin as they’re known in Top Secret. This way, it’s always possible today is the day your luck runs out.

Another novel idea is the way the game suggests playing with multiple Admins, each acting as both a GM and the director of a spy organization. Thus, in a two-Admin game, one could lead the CIA, the other the KGB and each direct characters who would engage in intrigues against each other.

The best thing in the original Top Secret box is the sample mission module, Operation: Sprechenhaltestelle. It details a neighborhood in a fictional European (maybe German?) city, full of spy activity of all kinds. The neighborhood is a highly intricate physical environment for the player characters to explore and act in. Reading it feels as if someone had tried to document the level design of a stealth-based videogame like Dishonored or Thief.

The design of the adventure presents an interesting, varied environment where you will always find something if you bother to look around. It showcases the strengths of an approach to roleplaying game design where the simulation and exploration of physical space is the main draw.