I started to feel that I didn’t know roleplaying games well enough so I came up with the plan to read a roleplaying game corebook for every year they have been published. Selection criteria is whatever I find interesting.

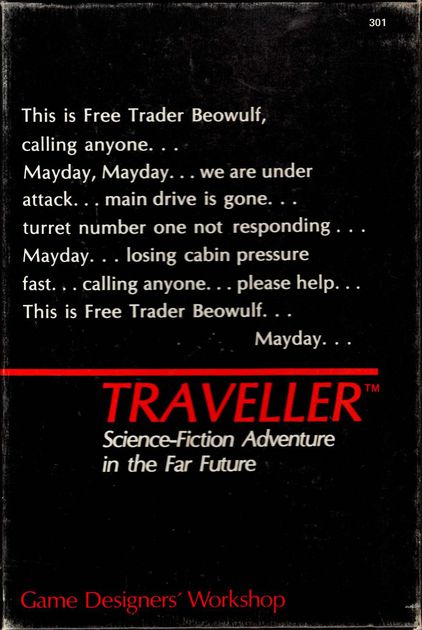

My reading project is already in the Nineties, but there was one Seventies game that I originally skipped that I wanted to return to: Traveller, from 1977. It’s referred to so often in game design discussions that I felt I had to read it.

Traveller is a hard science fiction game set in a far future of space travel and exploration. The characters are adventurers who can engage in trade, go to new worlds, chart territory and so on.

The original 1977 Traveller boxed set contains three books, none of which really explains what play concretely looks like. This is typical of early games but makes it a strange exercise to try to decipher the kind of game culture that works best for Traveller. There are tantalizing hints, however. At one point, we’re told that if a player uses an electronic calculator, the character should also be made to buy one in-game.

The game is clearly meant for a mathematically minded player. Indeed, this is part of it’s charm. Reading the books, I felt that I wasn’t included in the game’s target audience because I’m not mathematically inclined enough. However, I don’t hold this against Traveller.

Traveller is the only roleplaying game I’ve ever seen that uses the hexadecimal system, even if only for a cosmetic method of expressing character traits as a series of digits. At one point, you’re required to calculate a square root.

Despite having unusually complex maths, I don’t think Traveller is needlessly complicated. It’s based on the idea of procedurally created content, both in terms of character creation and exploration. These systems are extremely interesting and feel innovative even now. Indeed, it’s amazing to think that this game was published just a few years after roleplaying games came into existence.

Traveller’s most famous system is character creation. Instead of rolling stats or spending points you take your character through a career path. You accumulate experience, grow older, gain rank and may even die. Indeed, if your initial stats are weak, the book actually recommends making lethal choices so you can start over.

This is a fun idea, like a mini-game for solo players inside the bigger Traveller experience. Indeed, Traveller is explicitly designed to accommodate solo play.

The game doesn’t really feature a setting, although some details may be extrapolated from how different systems are described. There’s a Psionics Institute and people with psionic ability are reviled. Many space travellers use cutlasses. A person’s personal wealth greatly impacts travel comfort.

Instead, the procedural exploration system allows for randomly creating worlds and connections between. Although for aesthetic reasons I’m personally not a huge fan of procedurally created content, the idea of using it in a tabletop roleplaying game resonates. The main downside is that it requires fairly complex systems that may seem intimidating at first glance.

Some parts of Traveller are kinda funny. The section on encounters with humans seems to have been written by someone who finds human interaction to be a distasteful, remote process best glossed over. It’s immediately followed by a detailed section on animal encounters. It has received so much love, it feels like the main Traveller activity is to go to strange planets to be mauled by bears.

All in all, I found Traveller to be hugely impressive, well worth it’s status as a classic. Some parts make it clear that it was written before simple best practices in game design came to be but it compensates through sheer innovation.