In my A Game Per Year project, my goal has been to read one roleplaying game corebook for every year they’ve been published. However, I soon started to feel that it was hard to decipher how the games were really meant to be played. For this reason, I decided to start a parallel project, An Adventure Per Year, to read one roleplaying adventure for each year they’ve been published.

Masks of Nyarlathotep is a classic roleplaying campaign, originally published for Call of Cthulhu in 1984. Along with Enemy Within, its probably the best known and most acclaimed published campaign from that era.

The basic format for roleplaying especially in big, traditional games such as D&D and Call of Cthulhu is the campaign, a series of sessions that together build an ongoing, long-term experience. Because of this, publishing readymade campaigns feels like an obvious choice. And indeed, many of the adventures published for D&D 5th Edition essentially amount to a campaign because of their size.

Still, campaigns are hard to design and write compared to many other types of roleplaying supplements. Maybe because of this many games have seen only one or two. An example is Vampire: the Masquerade which saw Transylvania Chronicles (a crossover with Vampire: the Dark Ages) and Giovanni Chronicles but not much else on that scale.

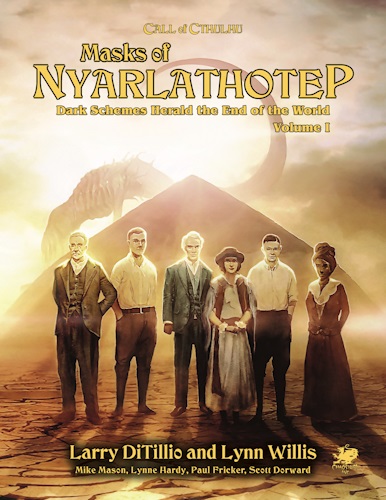

If we assume that creating a readymade campaign is a major undertaking, Masks of Nyarlathotep certainly supports that idea. I read it in the massively expanded 2018 slipcase edition although I also had the chance to leaf through The Complete Masks of Nyarlathotep, published in 1996.

The 2018 edition is over 650 pages long, split into two books. It also features a thick sheaf of handouts, a map and a GM screen, or a Keeper screen to use Call of Cthulhu’s own terminology. Despite their pagecount, the books are strongly oriented towards usability and playability. There’s little extraneous material even if the campaign clocks in at 50 pages per game session at my estimate.

In style, Masks of Nyarlathotep represents the pulp aesthetic common to many works derivative from H.P. Lovecraft’s stories. There’s a recurring concern over whether the (probably) American player characters can bring guns into countries that don’t want them.

The characters are investigators who get drawn into a world of cults, alien gods and world-ending rituals after they start investigating the death of a friend. The globetrotting adventure takes them from the U.S. to Egypt, Kenya, China, Australia and the U.K. In each locale, insane cultists worship their own version of Nyarlathotep. (Hence the title of the adventure.)

The campaign made me think about the concept of “player character” in roleplaying games. In the play culture I’m from, it’s assumed that you want to play a three-dimensional, complex person markedly different from your real self. You’re assumed to put effort into developing this character’s internal life and make choices that they would make while still keeping to the spirit of the game.

Because of this, character death is rare. Characters often do dumb things. Play time is spent on social play and exploring the interior lives of the characters.

This is an approach that works very badly with an adventure like Masks of Nyarlathotep. Like other Call of Cthulhu adventures I’ve read, it’s deadly. Characters are also assumed to take insane risks with their lives and jump into the most bizarre situations for the game to progress.

The player character type, the Investigator, is similar to the adventuring party in D&D in the sense that its a construction typical of these games that allows them to function. It’s also divergent from ordinary human experience. Doing the things that these characters do is hard to motivate if you approach your character psychologically.

Because of this, reading the adventure makes me think the play is assumed to be more superficial in character terms, where the character is a proxy that allows the player to access the content of the adventure. The character is not a field of exploration in itself, at least not to any major degree.

Of course, to many people, maybe even most people, who play Masks of Nyarlathotep this is the normal way to understand what character means in a roleplaying game. The idea of the Investigator challenges me because of my personal background of play.

The adventure is set in the Twenties. There’s been an attempt in the 2018 edition to make it less racist and more accessible to characters who are women and/or not white Americans. Still, reading it, I can’t help but wonder how differently many of the designed beats would work if you’d actually make characters who are Chinese or Egyptian. A lot of the situations play on the strangeness of the scenery and assume the characters are Western foreigners.

The difference between the older, original editions of Masks of Nyarlathotep and the new 2018 edition is stark. The original is a published campaign. The new edition is a monument. Its fortunate that the basic assumption of its design is still that people will run it. After all, it could have been just a nostalgia fest for old fans.