The things we call “roleplaying games” are books that tell you how to play and run actual roleplaying games. The game is what happens when you sit down with the other players and play.

I’m writing one of these books. Chernobyl mon amour (Tšernobyl, rakastettuni in Finnish) is a roleplaying game about love and radioactivity, set in the Chernobyl Zone of Alienation.

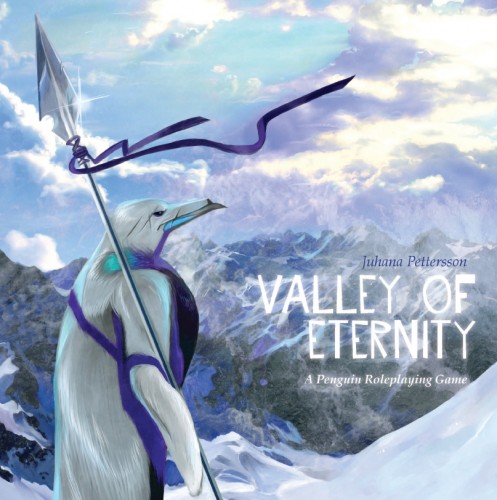

I’ve published one of these things before, Valley of Eternity, the game of epic penguin tragedy. However, that game was more traditional in form, so I could just do a book the way they’re usually done. However, with Chernobyl mon amour, my goal is to do a game that articulates the play culture that I live in, instead of adapting ideas to more generally understandable forms.

This has forced me to ask a simple question: What’s in a roleplaying game book? What does this book contain and what’s its purpose? What does it do?

The way I decided to answer this question for myself was this:

A roleplaying game is about experiencing the life of a character within a certain framework. The game book should provide three things.

1 – Instruction on how to play, how to be the character, and how to calibrate the experience so it works well for everyone.

2 – Instruction on how to run a game as the game master. How to make a good, interesting roleplaying game work.

3 – Provide fodder for the experiences the game is made of. An interesting setting, something beyond what the participants would be able to improvise on the spot. Details of scenes, supporting characters, locations, traditions, and other things the participants can use to make their game more particular and interesting.

Number three provides the fuel for numbers one and two.

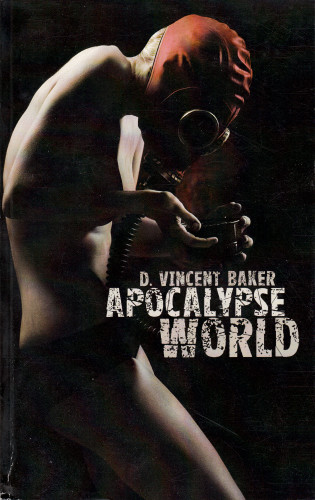

Other designers have answered this question very differently. D. Vincent Baker’s game Apocalypse World has numbers one and two, but no number three. It’s instruction has been codified into rules mechanics, and the book is essentially about how those rules mechanics work.

The Player’s Handbook and Dungeon Master’s Guide for various editions of D&D tend to be very weak on setting material as well, but with these games, we’re assumed to get the details of the setting separately. As books, they follow different ideas of organizing material than one-book games.

The book for Vampire: the Requiem is mostly about explaining it’s particular take on the idea of vampires. Since the game’s concept of vampires is very specific, explaining how it works takes a lot of space. Things like customs and social organization are explained in straight prose, while ideas related to conflict and what characters can do are codified into rules.

This is the model I followed with Valley of Eternity. It explains the basics of how to play and how to run a game, but most of the book is about explaining the game’s specific take on penguins and the world they live in. It too employed rules mechanics for handling some parts of the game experience.

Writing my new game, the comparison to Apocalypse World is striking in the sense that while both are “roleplaying game books”, they share almost no content of similar description. Of course, if you want to be philosophical, there are many parallels in terms of function, but in terms of what you see on a page they’re different.

I’m really interested to see the finished book when it comes out. Are you writing it in English or in Finnish? It sounds like the kind of project that could find an audience in the storygaming communities around the world.

The plan is to publish first in Finnish, and then do an English translation.